How to compute gradients in PyTorch

Notebooks and Slides

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Computing Gradients of Loss Functions

- Applying Gradient Descent to Least Squares

- More Complex Loss Functions: Building Neural Networks

Introduction

In our previous lecture, we explored gradient descent for minimizing the least squares objective. We saw how following the negative gradient leads us to the optimal solution, even for large-scale problems where direct methods fail. But least squares is just one example of a loss function. Modern machine learning employs many loss functions, each designed for specific tasks: cross-entropy for classification, Huber loss for robust regression, contrastive loss for similarity learning.

PyTorch provides a powerful system for computing gradients of any differentiable function built from its operations. This capability forms the foundation of modern deep learning, enabling automatic computation of gradients for complex neural networks. In this lecture, we examine how PyTorch’s automatic differentiation system works, starting with simple one-dimensional examples and building up to neural networks. We’ll see how the same principles that let us optimize least squares problems extend naturally to more complex settings.

Computing Gradients of Loss Functions

Let’s start with the simplest possible case: computing the gradient of a one-dimensional function. Consider the polynomial:

\[f(x) = x^3 - 3x\]This function has an analytical gradient:

\[\frac{d}{dx}f(x) = 3x^2 - 3\]While we can compute this derivative by hand, PyTorch offers a powerful alternative - automatic differentiation. Here’s how you use it.

import torch

# Create input tensor with gradient tracking

x = torch.tensor([1.0], requires_grad=True)

# Define the function

def f(x):

return x**3 - 3*x

# Forward pass: evaluating the function

y = f(x)

# Backward pass: computing the gradient

y.backward()

print(f"At x = {x.item():.1f}")

print(f"f(x) = {y.item():.1f}")

print(f"f'(x) = {x.grad.item():.1f}") # Should be 3(1)² - 3 = 0

This simple example reveals the key components of automatic differentiation:

- Gradient Tracking: We mark tensors that need gradients with

requires_grad=True - Forward Pass: PyTorch automatically records operations as we compute the function

- Backward Pass: The

backward()call computes gradients through the recorded operations - Gradient Access: The computed gradient is stored in the

.gradattribute

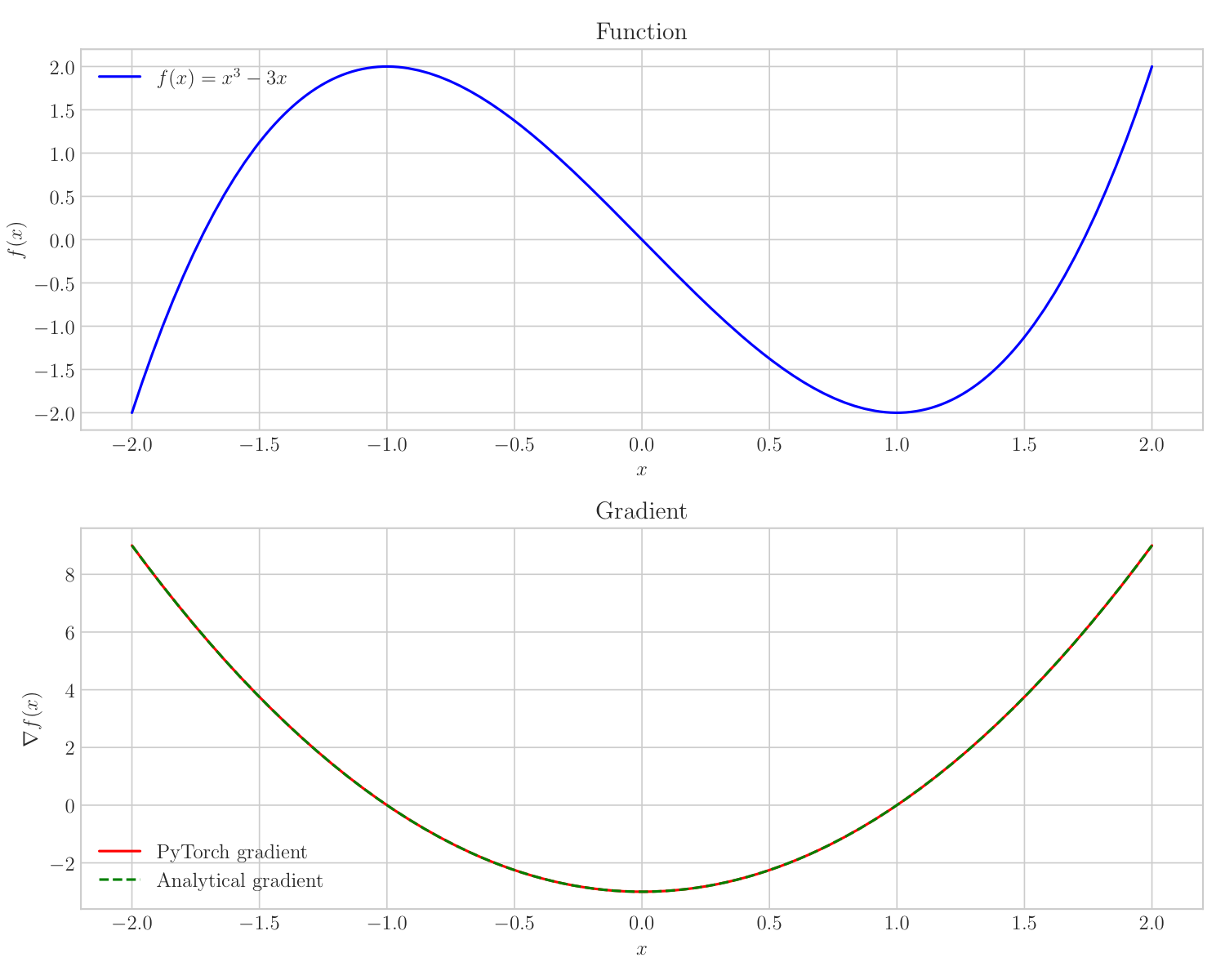

Let’s visualize how the analytic gradient and the gradient computed by PyTorch match up:

The top plot shows our function $f(x) = x^3 - 3x$, while the bottom plot compares PyTorch’s computed gradient (red solid line) with the analytical gradient $3x^2 - 3$ (green dashed line). They match perfectly, confirming that PyTorch computes exact gradients. To understand how PyTorch achieves this precision, we need to examine the machinery that powers its automatic differentiation system.

The top plot shows our function $f(x) = x^3 - 3x$, while the bottom plot compares PyTorch’s computed gradient (red solid line) with the analytical gradient $3x^2 - 3$ (green dashed line). They match perfectly, confirming that PyTorch computes exact gradients. To understand how PyTorch achieves this precision, we need to examine the machinery that powers its automatic differentiation system.

The Computational Graph

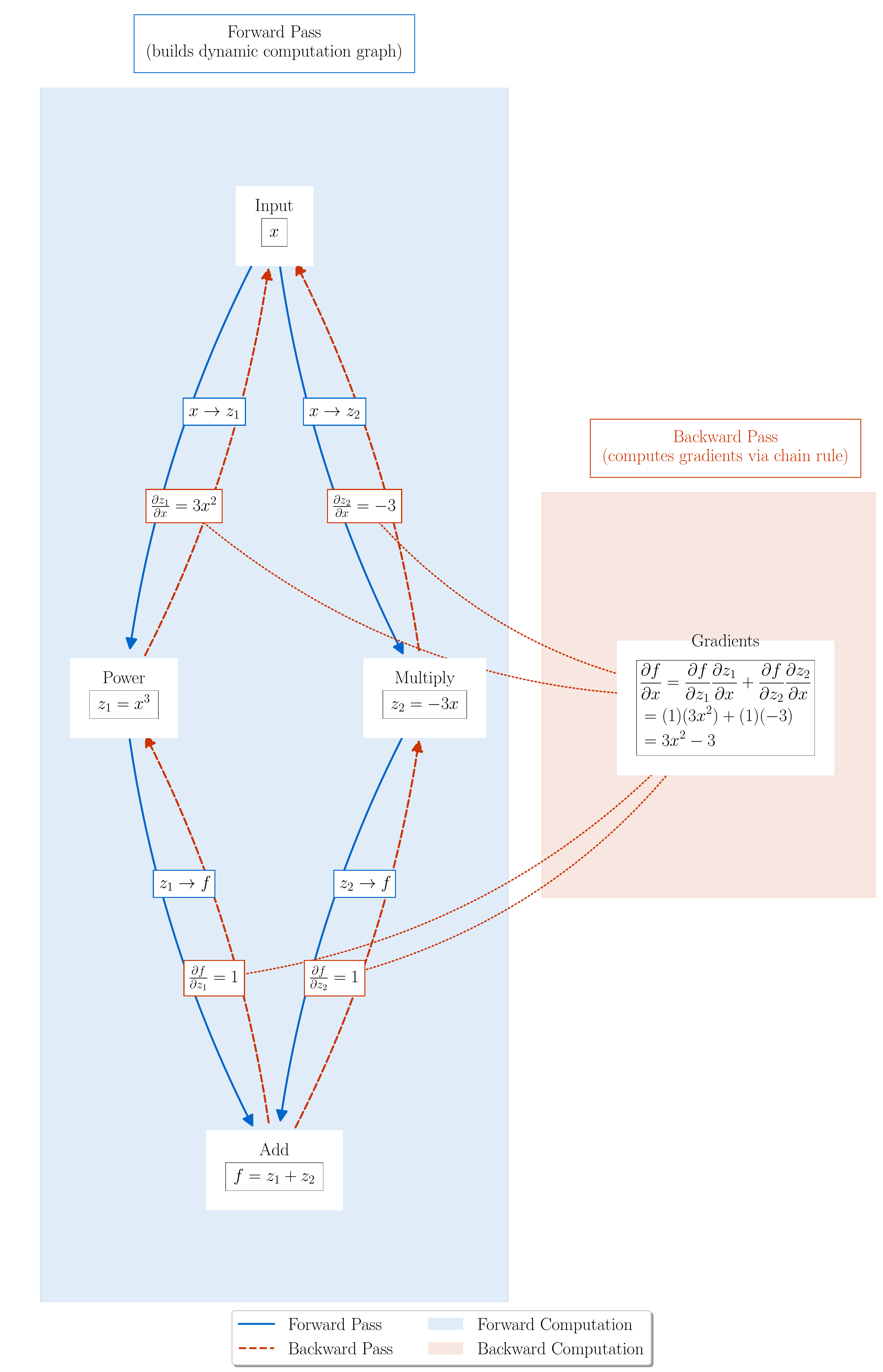

To understand how PyTorch computes these gradients, we need to examine the computational graph it builds during the forward pass:

The computational graph is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) where nodes represent operations and edges represent data flow. Each node stores:

- Its output value computed during the forward pass

- A function to compute local gradients (derivatives with respect to its inputs)

Each node in this graph represents an operation:

- Input node stores our value $x$

- Power node computes $z_1 = x^3$

- Multiply node computes $z_2 = -3x$

- Add node combines terms to form $f(x) = z_1 + z_2$

During the forward pass, PyTorch, records each operation in sequence, stores intermediate values, and maintains references between operations.

During the backward pass, PyTorch uses an efficient implementation of the chain rule that processes these nodes in reverse dependency order - what’s called a reverse topological sort. This means we start at the output and only process a node after we’ve handled all the nodes that depend on its result.

More specifically, to compute $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$ for output $f$ with respect to input $x$, we go through the following process:

Starting State:

- Initialize gradient at output node to 1 ($\frac{\partial f}{\partial f} = 1$)

- All other gradient accumulators start at $0$

Algorithm: The system performs a reverse topological sort traversal of the graph. At each node:

- Compute local gradients using stored forward-pass values

- Multiply incoming gradient by local gradient (chain rule)

- Add result to gradient accumulators of input nodes

For the polynomial $f(x) = x^3 - 3x$, this process looks like this:

Output Node ($f = z_1 + z_2$):

- $\frac{\partial f}{\partial f} = 1$

- Local gradients: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_1} = 1$, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2} = 1$

- Propagate to $z_1$, $z_2$ nodes: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_1} = 1$, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2} = 1$

Power Node ($z_1 = x^3$):

- Incoming gradient: 1

- Local gradient: $\frac{\partial z_1}{\partial x} = 3x^2$

- Contribute to x’s gradient accumulator: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \mathrel{+}= (1)(3x^2)$

Multiply Node ($z_2 = -3x$):

- Incoming gradient: 1

- Local gradient: $\frac{\partial z_2}{\partial x} = -3$

- Contribute to x’s gradient accumulator: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \mathrel{+}= (1)(-3)$

Input Node ($x$): [accumulation needed because x has two outgoing edges]

- Accumulated gradients from both paths: $3x^2$ and $-3$

- Final gradient (sum of all paths): $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = 3x^2 - 3$

From this example, it should be clear that the algorithm is completely mechanical - each node only needs to know its local gradient function, and the graph structure determines where accumulation is needed (at nodes with multiple outgoing edges). The memory complexity is O(n) where n is the number of nodes, as we store one gradient accumulator per node. The time complexity is also O(n) as we visit each node exactly once and perform a fixed amount of work per node.

While we state this result for a one function of a single variable, it should be clear that it generalizes. For example, to handle multiple inputs, we track separate gradient accumulators for each input. For vector-valued functions, gradients become Jacobian matrices. Higher derivatives can be computed by applying the same process to the gradient computation graph.

Important Requirement: This graph structure explains a crucial requirement: we can only compute gradients through operations that PyTorch implements. The framework needs to know both (1) how to compute the operation (forward pass) and (2) how to compute its derivative (backward pass). Common operations like addition (+), multiplication (*), and power (**) are all implemented by PyTorch. Even when we use Python’s standard operators, we’re actually calling PyTorch’s overloaded versions that know how to handle both computation and differentiation.

Two Methods for Gradient Computation: backward() and autograd.grad()

PyTorch provides two ways to compute gradients, each designed for different use cases. Let’s see how they work using our polynomial example:

# Our familiar polynomial f(x) = x³ - 3x

x = torch.tensor([1.0], requires_grad=True)

z1 = x**3 # First intermediate value

z2 = -3*x # Second intermediate value

f = z1 + z2 # Final output

During this forward pass, PyTorch builds a computational graph dynamically. Each operation adds nodes and edges to the graph, tracking how values flow through the computation. The graph in our visualization shows exactly this process - from input x through intermediate values z₁ and z₂ to the final output f.

The standard method uses backward():

f.backward() # Compute gradient

print(x.grad) # Access gradient through .grad attribute

When you call backward(), PyTorch (1) creates a new graph for the gradient computation, (2) computes gradients by flowing backward through this graph, (3) stores results in the .grad attributes of input tensors, and (4) discards both graphs to free memory.

You can inspect intermediate values during computation:

print(z1.data) # See value of x³

print(z2.data) # See value of -3x

By default, PyTorch only stores gradients for leaf tensors (inputs where we set requires_grad=True). This saves memory while still giving us the gradients we need for optimization. If you need gradients for intermediate values, you can request them:

z1.retain_grad() # Tell PyTorch to store this gradient

f.backward()

print(z1.grad) # Now we can see how f changes with z₁

The second method, torch.autograd.grad(), gives us more direct control:

x = torch.tensor([1.0], requires_grad=True)

f = x**3 - 3*x

grad = torch.autograd.grad(f, x)[0] # Get gradient directly

This method (1) returns the gradient immediately as a new tensor (2) lets you compute gradients with respect to any tensor in your computation (3) creates and discards the computational graph in one step

Both methods compute exactly the same gradients - they just offer different ways to access them. Use backward() when you want gradients stored in your tensors, and autograd.grad() when you want direct access to specific gradients.

The computational graph we drew earlier shows exactly how these gradients are computed, combining the derivatives at each step using the chain rule. The power of PyTorch’s automatic differentiation is that it handles this process automatically, letting us focus on designing our computations rather than deriving gradients by hand.

Common Pitfalls in Automatic Differentiation

Several common mistakes can break gradient computation or cause memory issues:

1. In-place Operations

In-place operations can break gradient computation by modifying values needed for the backward pass:

# Create a tensor with gradients enabled

x = torch.tensor([4.0], requires_grad=True)

# Compute the square root. For sqrt, the backward pass needs the original output

y = torch.sqrt(x) # y is 2.0, and sqrt's backward uses this value

# Show the gradient function before modification

print("Before in-place op, y.grad_fn:", y.grad_fn)

# Define another operation that uses y

z = 3 * y

try:

# In-place modify y. This alters the saved value needed by the sqrt backward

y.add_(1) # Now y becomes 3.0

print("After in-place op, y.grad_fn:", y.grad_fn) # The grad_fn is now None

# Attempt to compute gradients. This will trigger a RuntimeError

z.backward()

print("This line won't be reached")

except RuntimeError as e:

print(f"Error with in-place operation: {e}")

print("\nWhy did this happen?")

print("The in-place operation (y.add_(1)) modified sqrt's output")

print("This invalidated the saved value needed to compute the gradient:")

print("d/dx sqrt(x) = 1/(2*sqrt(x))")

# Correct way: use out-of-place operations

x = torch.tensor([4.0], requires_grad=True)

y = torch.sqrt(x)

# Instead of modifying y in-place, create a new tensor

y = y + 1

z = 3 * y

z.backward() # This works fine

print("\nCorrect gradient:", x.grad)

# Before in-place op, y.grad_fn: <SqrtBackward0 object at 0x107e174f0>

# After in-place op, y.grad_fn: <AddBackward0 object at 0x107eb24d0>

# Error with in-place operation: one of the variables needed for gradient computation has been modified by an inplace operation: [torch.FloatTensor [1]], which is output 0 of SqrtBackward0, is at version 1; expected version 0 instead. Hint: enable anomaly detection to find the operation that failed to compute its gradient, with torch.autograd.set_detect_anomaly(True).

# Why did this happen?

# The in-place operation (y.add_(1)) modified sqrt's output

# This invalidated the saved value needed to compute the gradient:

# d/dx sqrt(x) = 1/(2*sqrt(x))

# Correct gradient: tensor([0.7500])

2. Memory Management

The torch.no_grad() context manager is crucial for memory efficiency:

# Create large tensors

X = torch.randn(1000, 1000, requires_grad=True)

y = torch.randn(1000)

def compute_loss(X, y):

return ((X @ X.t() @ y - y)**2).sum()

# Memory inefficient: tracks all computations

loss1 = compute_loss(X, y)

# Memory efficient: no gradient tracking during evaluation

with torch.no_grad():

loss2 = compute_loss(X, y)

print(f"Gradient tracking: {loss1.requires_grad}")

print(f"No gradient tracking: {loss2.requires_grad}")

# Gradient tracking: True

# No gradient tracking: False

3. Gradient Accumulation

When training with multiple backward passes, remember to zero gradients:

x = torch.tensor([1.0], requires_grad=True)

optimizer = torch.optim.SGD([x], lr=0.1)

for _ in range(2):

y = x**2

# Wrong: gradients accumulate

y.backward(retain_graph=True) # Need retain_graph=True for multiple backward passes

print(f"Accumulated gradient: {x.grad}")

# Correct: zero gradients before backward

optimizer.zero_grad()

y = x**2 # Need to recompute y since previous backward consumed the graph

y.backward()

print(f"Clean gradient: {x.grad}")

optimizer.step()

# Accumulated gradient: tensor([2.])

# Clean gradient: tensor([2.])

# Accumulated gradient: tensor([3.6000])

# Clean gradient: tensor([1.6000])

These patterns become especially important when training deep networks where mistakes can be harder to debug.

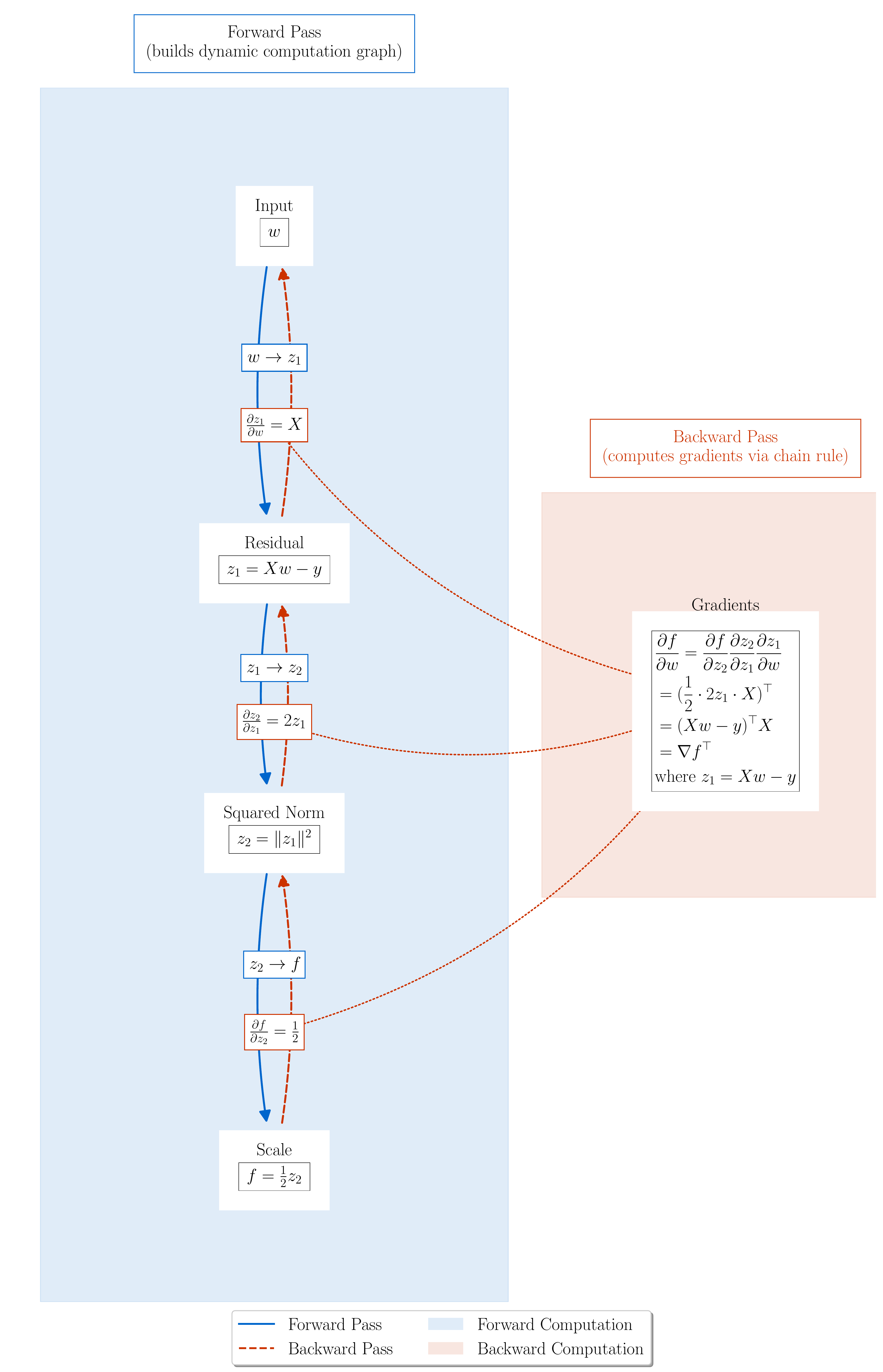

Beyond Single Variables: Least Squares

Let’s examine how PyTorch handles gradient computation for the least squares problem, where we minimize $f(\mathbf{w}) = \frac{1}{2}|\mathbf{X}\mathbf{w} - \mathbf{y}|^2$ for data matrix $\mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}$ and observations $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$. Like our polynomial example, PyTorch builds and traverses a computational graph to compute gradients automatically.

The computational graph for least squares reveals how PyTorch decomposes this multivariate optimization into elementary operations. Each node performs a specific computation in the chain that leads to our final loss:

During the forward pass, the graph computes:

- Input node stores parameter vector $\mathbf{w}$

- Residual node computes $\mathbf{z}_1 = \mathbf{X}\mathbf{w} - \mathbf{y}$

- Square norm node computes $z_2 = |\mathbf{z}_1|^2$

- Scale node produces final loss $f = \frac{1}{2}z_2$

In this multidimensional case, we follow the same algorithm for computing the gradient of $f$ as we did in the 1d case, but with a slight twist. As we traverse the graph in reverse order we compute and store the total derivatives or Jacobians of the intermediate nodes and multiply them out. In particular, we compute the Jacobians $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2}, \frac{\partial z_2}{\partial \mathbf{z}_1}, \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}_1}{\partial \mathbf{w}}$ and multiply them out to get the total derivative $\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{w}}$, which is a $1 \times p$ row matrix. The connection with the gradient of $f$ is that the total derivative is simply the tranpose of the gradient. More specifically, we have:

Output Node ($f = \frac{1}{2}z_2$):

- Incoming gradient: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial f} = 1$ (scalar)

- Total derivative: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2} = \frac{1}{2}$ (scalar)

- Propagate to $z_2$ node: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2} = \frac{1}{2}$ (1×1 matrix)

Square Norm Node ($z_2 = |\mathbf{z}_1|^2$):

- Incoming total derivative: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2} = \frac{1}{2}$ (1×1 matrix)

- Local total derivative: $\frac{\partial z_2}{\partial \mathbf{z}_1} = 2\mathbf{z}_1^\top$ (1×n matrix)

- Propagate to $\mathbf{z}_1$ node: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{z}_1} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2}\frac{\partial z_2}{\partial \mathbf{z}_1} = \mathbf{z}_1^\top$ (1×n matrix)

Residual Node ($\mathbf{z}_1 = \mathbf{X}\mathbf{w} - \mathbf{y}$):

- Incoming total derivative: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{z}_1} = \mathbf{z}_1^\top$ (1×n matrix)

- Local total derivative: $\frac{\partial \mathbf{z}_1}{\partial \mathbf{w}} = \mathbf{X}$ (n×p matrix)

- Total derivative to $\mathbf{w}$ node: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{w}} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{z}_1}\frac{\partial \mathbf{z}_1}{\partial \mathbf{w}} = \mathbf{z}_1^\top\mathbf{X}$ (1×p matrix)

Input Node ($\mathbf{w}$):

- Total derivative: $\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{w}} = \mathbf{z}_1^\top\mathbf{X}$ (1×p matrix)

- Convert to gradient: $\nabla f = (\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{w}})^\top = \mathbf{X}^\top\mathbf{z}_1$ (p×1 matrix)

This computation reveals why the transpose appears: the chain rule naturally produces the total derivative $\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{w}}$ as a row vector (1×p matrix), but we conventionally write the gradient $\nabla f$ as a column vector (p×1 matrix). The transpose converts between these representations.

The full chain rule expansion shows how the total derivative combines all computations:

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{w}} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial z_2} \frac{\partial z_2}{\partial \mathbf{z}_1} \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}_1}{\partial \mathbf{w}} = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 2\mathbf{z}_1^\top \cdot \mathbf{X} = \mathbf{z}_1^\top\mathbf{X}\]And the gradient is its transpose:

\[\nabla f = \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{w}}^\top = \mathbf{X}^\top\mathbf{z}_1 = \mathbf{X}^\top(\mathbf{X}\mathbf{w} - \mathbf{y})\]This computation happens automatically in PyTorch through the computational graph structure, with each node computing its local total derivatives. The graph structure determines where accumulation is needed (at nodes with multiple outgoing edges), and the mechanical process of backpropagation handles the rest.

From the perspective of code, nothing changes. We still define the loss function as before, and call loss.backward() to compute the gradient.

# Convert data to PyTorch tensors

X = torch.tensor(X_data, dtype=torch.float32)

y = torch.tensor(y_data, dtype=torch.float32)

w = torch.zeros(X.shape[1], requires_grad=True) # Initialize weights

# Compute loss

predictions = X @ w

loss = 0.5 * torch.mean((predictions - y)**2)

# Compute gradient

loss.backward()

print(f"PyTorch gradient: {w.grad}")

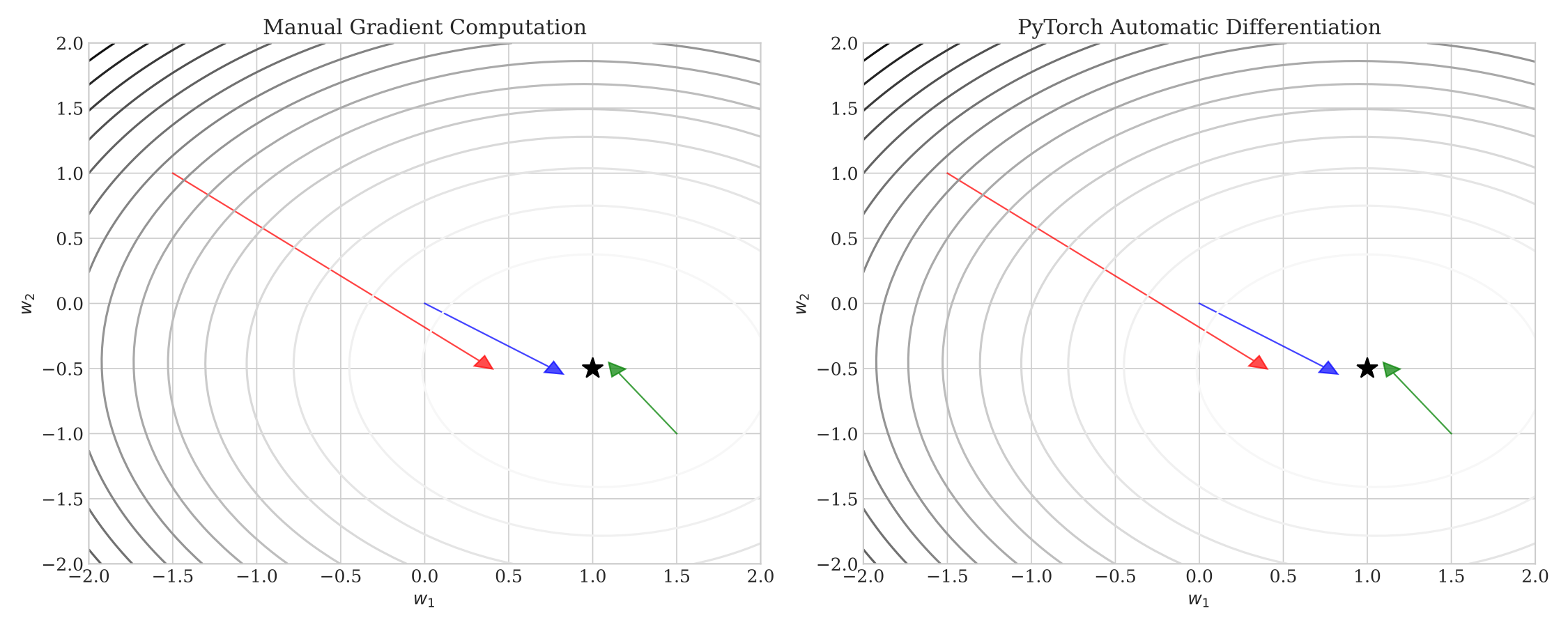

To verify that PyTorch computes the correct gradient, we can compare it with our manual calculation:

The figure shows the contours of the least squares loss function for a simple 2D problem. At three different points (marked in red, blue, and green), we compute gradients using both manual calculation (left) and PyTorch’s automatic differentiation (right). The arrows show the negative gradient direction at each point - the direction of steepest descent. The gradient computed by PyTorch matches the manual calculation, confirming that PyTorch computes the correct gradient.

Applying Gradient Descent to Least Squares

Now that we know how to compute gradients via autodifferentiation, let’s use them to find the optimal weights in a least squares problem. First let’s recall how we manually ran gradient descent on the least squares loss

\[f(w) = \frac{1}{2}\|Xw - y\|_2^2\]In the previous lecture, we derived the gradient manually:

\[\nabla f(w) = X^\top(Xw - y)\]# Manual gradient descent

def manual_gradient(X, y, w):

# Gradient of 0.5 * ||Xw - y||^2 / n is X^T(Xw - y)

return X.T @ (X @ w - y)

w_manual = torch.zeros(2) # initialize the weights with zeros

for step in range(max_iter):

grad = manual_gradient(X, y, w_manual)

w_manual = w_manual - alpha * grad

Now let’s compare to the PyTorch implementation, which uses backward() to compute the gradient.

# PyTorch gradient descent

w_torch = torch.zeros(2, requires_grad=True) # initialize the weights with zeros and track gradients

for step in range(max_iter):

## Forward pass

pred = X @ w_torch # compute the predictions

loss = 0.5 * torch.sum((pred - y)**2) # compute the loss

## Backward pass

loss.backward() # compute the gradient

## Update weights

with torch.no_grad(): # Do not modify the computational graph

w_torch -= alpha * w_torch.grad # update the weights

w_torch.grad.zero_() # reset the gradient to zero to avoid accumulation

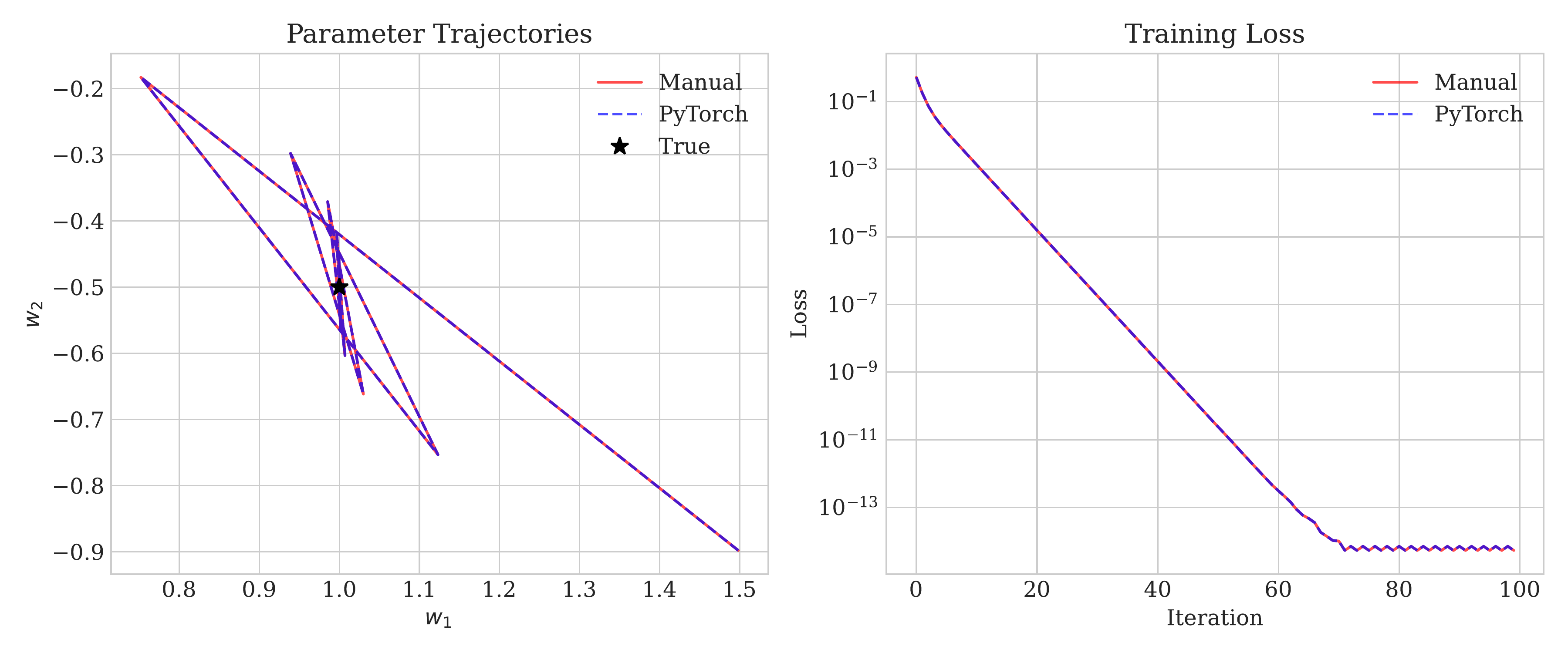

We ran both implementations on the same data and found the following results:

Both methods (1) converge to the same optimal weights, (2) follow identical trajectories, and (3) achieve the same final loss value. This agreement confirms that PyTorch computes exact gradients, matching our manual calculations. The difference lies in convenience - PyTorch handles the gradient computation automatically, while we had to derive and implement the gradient formula manually.

For a more complex example, let’s implement logistic regression on the MNIST dataset. We’ll explore this in detail in the following section.

More Complex Loss Functions: Building Neural Networks

Linear regression maps inputs to outputs through a single transformation: $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{X}\mathbf{w}$. Neural networks extend this idea by stacking multiple transformations, enabling them to learn more complex patterns. Let’s examine how PyTorch implements these layered models.

Consider binary classification. Instead of a single linear transformation, we compose (1) a linear transformation to create hidden features, (2) a nonlinear activation to introduce nonlinearity, (3) another linear transformation to produce predictions, and (4) a final nonlinearity to output probabilities. Graphically, this looks like:

Input → Linear₁ → Tanh → Linear₂ → Sigmoid → Output

ℝᵈ ℝʰˣᵈ ℝʰ ℝ¹ˣʰ [0,1] [0,1]

Mathematically, for input $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d$:

-

First transformation creates hidden features $\mathbf{h} \in \mathbb{R}^h$: \(\mathbf{h} = \tanh(\mathbf{W}_1\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}_1)\) where $\mathbf{W}_1 \in \mathbb{R}^{h \times d}$ and $\mathbf{b}_1 \in \mathbb{R}^h$

-

Second transformation produces probability $p \in [0,1]$: \(p(y=1|\mathbf{x}) = \sigma(\mathbf{w}_2^\top\mathbf{h} + b_2)\) where $\mathbf{w}_2 \in \mathbb{R}^h$ and $b_2 \in \mathbb{R}$

PyTorch’s nn.Module provides a natural way to implement this architecture:

class BinaryClassifier(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim=2, hidden_dim=10):

super().__init__()

# First transformation: ℝᵈ → ℝʰ

self.linear1 = nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim)

# Second transformation: ℝʰ → ℝ

self.linear2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1)

def forward(self, x): # x shape: [batch_size, input_dim]

# Hidden features: [batch_size, hidden_dim]

h = torch.tanh(self.linear1(x))

# Output probability: [batch_size, 1]

return torch.sigmoid(self.linear2(h))

Each nn.Module layer stores both a weight matrix and a bias vector. When we call the forward method, the layer computes the hidden features and then applies the nonlinearity to produce the output probability. The code initializes the weights and biases automatically, and registers them for gradient computation. This modular design lets us build complex models by composing simple layers, let PyTorch handle parameter management, and focus on model architecture rather than implementation details. For example, we can swap out the nonlinearity (the $\tanh$) with a different activation function to try out different architectures.

MNIST Classification Example

In this section, we design a classifier for the MNIST digit classification task using logistic regression (a neural network with no hidden layers) and a neural network with one hidden layer. We focus on binary classification to determine whether a digit is odd or even. This demonstrates how PyTorch allows us to swap out models and losses to try out different architectures with just a few lines of code.

The implementation uses torchvision.datasets.MNIST for data loading and transforms.Normalize for preprocessing. Input images are normalized with MNIST’s statistics (mean=0.1307, std=0.3081):

transform = transforms.Compose([

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize((0.1307,), (0.3081,))

])

train_dataset = datasets.MNIST('./data', train=True, transform=transform)

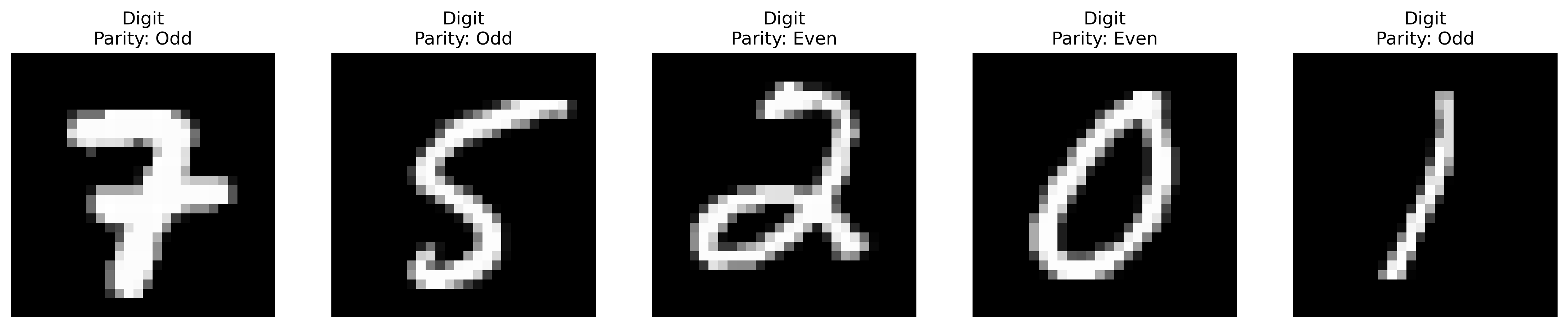

Examples of MNIST digits. The models aims to identify the parity (odd/even) of each digit.

Examples of MNIST digits. The models aims to identify the parity (odd/even) of each digit.

The objective uses binary cross-entropy loss to measure the discrepancy between predicted probabilities and true labels:

\[L(w) = -\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n [y_i \log p(y_i|x_i) + (1-y_i)\log(1-p(y_i|x_i))]\]where $y_i$ indicates whether digit $i$ is odd (1) or even (0), and \(p(y_i \mid x_i)\) is the model’s predicted probability. As before:

\[p(y_i = 1 \mid x_i) = \sigma(\text{model}(x_i)),\]where we $\sigma$ is the sigmoid function and we use one of two models. First, logistic regression provides a baseline using a single linear layer:

class Logistic(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim):

super().__init__()

self.linear = torch.nn.Linear(input_dim, 1, bias=False)

def forward(self, x):

return torch.sigmoid(self.linear(x))

The neural network extends this with a hidden layer and ReLU activation to learn nonlinear decision boundaries:

class SimpleNN(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.fc1 = torch.nn.Linear(784, 32)

self.fc2 = torch.nn.Linear(32, 1)

def forward(self, x):

h = torch.relu(self.fc1(x))

return torch.sigmoid(self.fc2(h))

We then train the model using PyTorch’s automatic differentiation to compute gradients of the binary cross-entropy loss. The training loop follows three essential steps:

- Forward Pass: Compute predictions and loss

- Feed data through the model to get predictions

- Calculate loss between predictions and true labels

- Backward Pass: Compute gradients

- Call

loss.backward()to compute gradients through the computational graph - PyTorch automatically handles the chain rule through all operations

- Call

- Parameter Update: Apply gradients

- Zero out existing gradients to prevent accumulation from previous steps

- Update each parameter using the computed gradients

- The update follows $w \leftarrow w - \alpha \nabla L(w)$ where $\alpha$ is the learning rate

Here’s the implementation:

# Define the loss function

criterion = torch.nn.BCELoss()

def train_model(model, X_train, y_train, X_val, y_val, alpha=0.01, n_steps=1000):

for step in range(n_steps):

# Forward pass

y_pred = model(X_train)

loss = criterion(y_pred.squeeze(), y_train)

# Backward pass

loss.backward()

# Update parameters

with torch.no_grad(): # Do not modify the computational graph

for param in model.parameters():

param -= alpha * param.grad # update the parameters

param.grad.zero_() # reset the gradient to zero to avoid accumulation

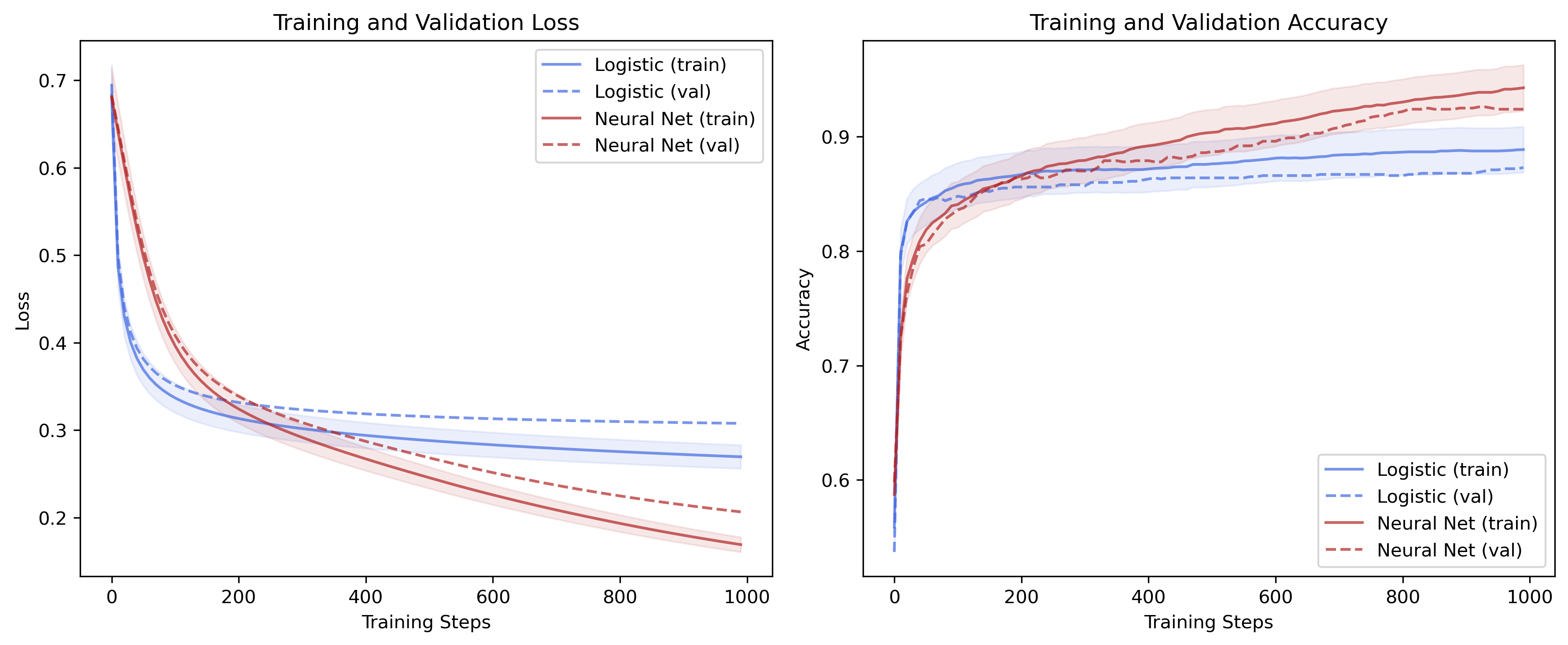

The neural network achieves 92.40% test accuracy versus logistic regression’s 87.30%. This gap results from the neural network’s ability to learn nonlinear decision boundaries.

Training curves for logistic regression (blue) and neural network (red). The neural network learns faster and reaches higher accuracy.

Training curves for logistic regression (blue) and neural network (red). The neural network learns faster and reaches higher accuracy.