Using min cut to determine activation recomputation strategy

Standard automatic differentiation saves many intermediate “activations” from the forward pass to be reused during the backward pass. This can be memory-intensive. Recomputation, or activation checkpointing, is a technique that saves memory by re-calculating these activations during the backward pass instead of storing them. While this suggests a trade-off between memory and compute, a fusing compiler like NVFuser changes the calculation.

For a chain of pointwise operations (e.g., add, relu, cos), a fusing compiler can execute them in a single GPU kernel. The performance of this kernel is limited by memory bandwidth, the speed of reading from and writing to the GPU’s global memory (HBM), not by the arithmetic operations themselves. This means that recomputing a sequence of fused pointwise operations is nearly free, provided the initial input to the sequence is available.

Thus, the problem of choosing which activations to save in the forward pass is about minimizing memory traffic, not necessarily minimizing FLOPs. I came across a very clever strategy for doing this in a blog post by Horace He. There, Horace frames the problem as a “min cut” on the computation graph and sees some nice improvements. I recommend reading the post for details. Here I’ll mainly work out some details that I was confused about in Horace’s original post. 1

Backward and forward passes

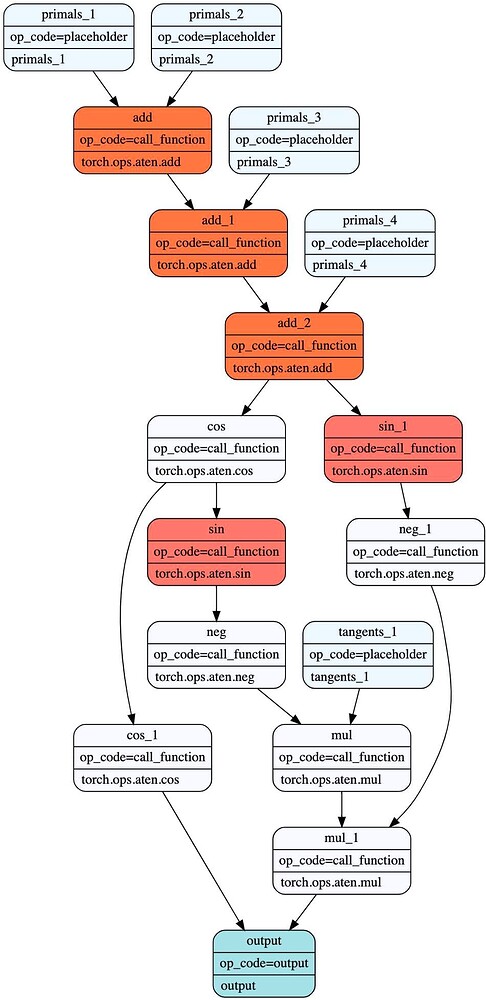

Consider the function f(a,b,c,d) = cos(cos(a+b+c+d)). Let z = a+b+c+d. The forward pass computes z, then cos(z), then y = cos(cos(z)).

The chain rule dictates what the backward pass needs. To compute the gradients, it requires the intermediate values, or “activations,” z and cos(z) to calculate sin(z) and sin(cos(z)):

dy = incoming ∂L/∂y

dcos = dy * (-sin(x.cos()))

dx = dcos * (-sin(x))

da,db,dc,dd = dx

A standard autograd system, as shown in the first figure, would save the z and cos(z), require 2 reads and 2 writes. This ensures the values are available for the backward pass.

This is a safe but suboptimal strategy. The total data transferred between the forward and backward passes for this strategy is the size of two tensors. We can do better. The key insight is that if we save only z (the output of add_2), we can recompute cos(z) on-the-fly inside the backward pass’s fused kernel. This halves the memory traffic.

The Min-Cut Formulation

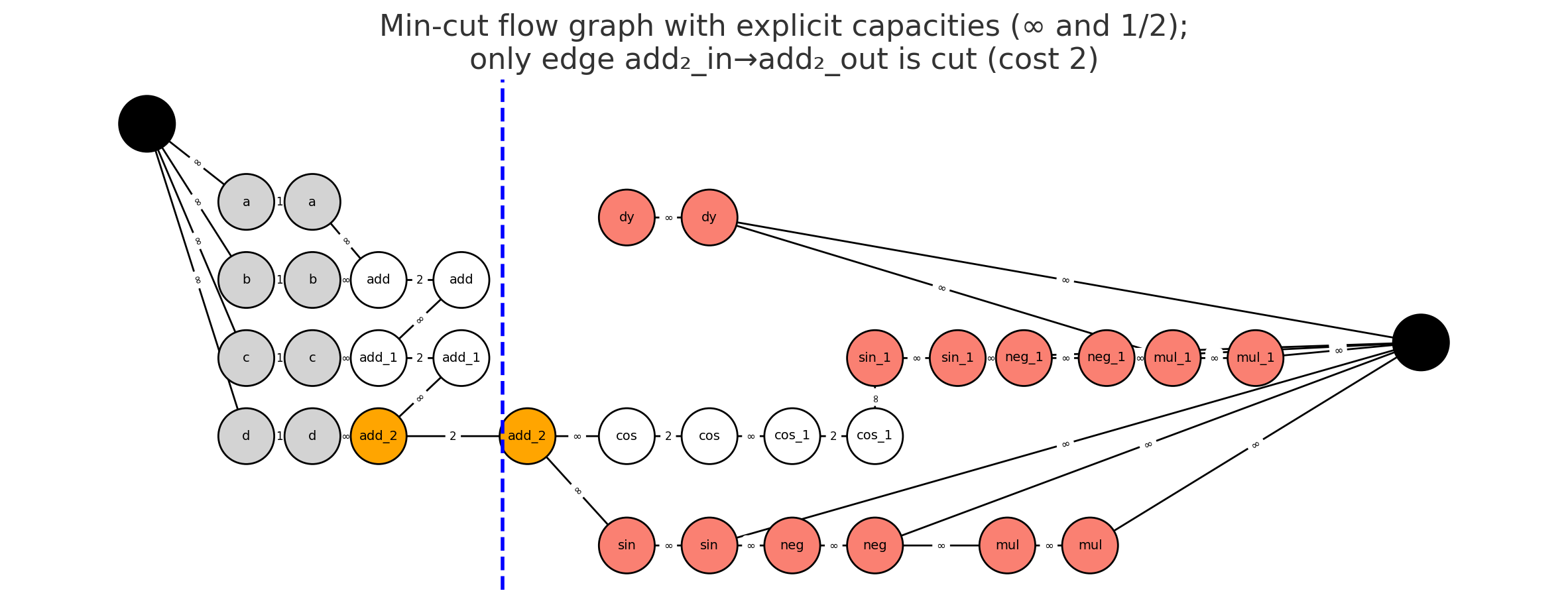

To find this optimal set of checkpointed tensors automatically, we model the problem as finding a minimum cut in a graph.

-

The Graph: We construct a graph representing the full forward and backward computation. We add a virtual source,

SRC, and a virtual sink,SNK. - The Source and Sink Sets:

- The source set represents the beginning of the forward pass. The

SRCnode is connected to all initial inputs of the model (e.g.,a, b, c, d). - The sink set represents the operations that must run in the backward pass. An operation must be in the backward pass if it depends on the incoming gradient. This set of operations is called the tangent closure. In the figures, these are the red nodes. The

SNKnode is connected to all nodes in the tangent closure.

- The source set represents the beginning of the forward pass. The

-

Edges and Costs: The problem is transformed into a standard edge-cut problem via node splitting. Every operation node

vis split into two nodes,v_inandv_out, connected by an edge.- Split Edges (

v_in -> v_out): These are the only edges with a finite cost, or. The cost of this edge is the cost of checkpointing the tensorv.Cost = 2 * B(v)for an intermediate activation. This cost represents onewriteto global memory and onereadfrom it.Cost = 1 * B(v)for a forward pass input that already exists in global memory. This cost represents just oneread. Here,B(v)is the size of the tensor in bytes.

- Data-Flow Edges (

u_out -> v_in): Edges representing the flow of data between operations have infinite cost. This models our assumption that recomputation within a fused kernel is free.

- Split Edges (

-

The Cut: The min-cut algorithm finds the set of edges with the minimum total cost that must be severed to separate

SRCfromSNK. Because only the split edges have finite cost, the algorithm will only sever those.Mathematically, the algorithm solves for the

\[\text{minimize} \sum_{(u \to v) \in \text{cut}} \text{cost}(u \to v)\]s-tcut 2 with minimum total cost:The sum is over all edges in the cut. Since data-flow edges have infinite cost, a minimal cut will only ever consist of the finite cost”split edges.” The problem is thus equivalent to finding the cheapest set of split edges to sever.

An edge

v_in -> v_outbeing cut means we have decided to pay its cost and checkpoint the tensorv. The nodes whose edges are cut are colored orange. Nodes on theSRCside of the cut are inputs. Nodes on theSNKside are either part of the mandatory tangent closure (red) or are operations that will be recomputed (white).

For our example, the algorithm compares the costs of all possible cuts:

- Cut at

add_2: Severs theadd_2_in -> add_2_outedge. Cost =2B. - Cut at

cosandcos_1: Severs two edges. Cost =2B + 2B = 4B. - Cut at the inputs: Severs four edges. Cost =

1B + 1B + 1B + 1B = 4B.

The minimum cost is 2B, corresponding to cutting only the add_2 edge. This means the optimal strategy is to checkpoint add_2 (orange), recompute cos and cos_1 (white), and feed the results to the tangent closure (red).

Thus, the min-cut formulation finds the checkpointing strategy that minimizes memory traffic under the fused computation model. These min-cut problems can be solved efficiently with standard max-flow algorithms.

-

See also this paper, which Horace pointed me to. ↩

-

An

s-tcut is a set of edges whose removal disconnects all paths fromSRCtoSNK. ↩