Adagrad, Adam, and AdamW

Table of contents

Motivation

SGD performs poorly when input features have varying scales or the loss function $L(w)$ is poorly conditioned. Poor conditioning means the Hessian matrix $\nabla^2 L(w)$ has eigenvalues with widely different magnitudes, measured by the condition number $\kappa = \lambda_{\max} / \lambda_{\min}$. The loss landscape then exhibits elongated valleys. SGD may oscillate across steep dimensions while progressing slowly along flat dimensions. For deep learning models, parameter gradients often vary significantly across layers, exacerbating this issue.

Consider a quadratic problem

\[L(w) = \frac{1}{2}(h_1 w_1^2 + h_2 w_2^2)\]with $h_1 \gg h_2 > 0$. The condition number is $\kappa = h_1/h_2$. SGD requires a learning rate $\alpha < 2/h_1$ for stability. This choice yields slow convergence for $w_2$, proportional to $(1 - \alpha h_2)^k \approx (1 - h_2/h_1)^k$, which is slow when $\kappa$ is large.

Adaptive optimization methods address this by assigning each parameter $w_i$ its own learning rate. These methods typically scale the learning rate for $w_i$ inversely proportional to a function of its historical gradient magnitudes $g_{t,i}$. Parameters with consistently large gradients receive smaller effective learning rates, while those with small gradients receive larger ones. This automatically handles varying feature scales and improves performance on ill-conditioned problems.

Adagrad (Duchi et al., 2011) was an early adaptive method. It accumulates squared gradients to scale the learning rate. RMSProp (Tieleman & Hinton, 2012) improved Adagrad by using a moving average of squared gradients, preventing learning rates from vanishing. Adam (Kingma & Ba, 2015) combined RMSProp’s adaptive rates with momentum and bias correction. AdamW (Loshchilov & Hutter, 2019) modified Adam’s weight decay implementation for potentially better regularization. Adam is widely used, particularly for training large language models.

Algorithm Definitions

Adagrad

Adagrad adapts the learning rate for each parameter $w_i$ based on the history of its gradients $g_{t,i} = [\nabla \ell(w_{t-1}, z_t)]_i$. At iteration $t$, Adagrad first computes the sum of squared gradients for parameter $i$ up to iteration $t$:

\[G_{t,ii} = \sum_{j=1}^{t} g_{j,i}^2\]The update rule for parameter $w_{t,i}$ uses this sum to scale the global learning rate $\alpha$:

\[w_{t,i} = w_{t-1,i} - \frac{\alpha}{\sqrt{G_{t,ii} + \epsilon}} \cdot g_{t,i}\]Here, $\epsilon$ is a small constant (e.g., $10^{-8}$) for numerical stability. The term $G_{t,ii}$ causes the effective learning rate for $w_i$ to decrease as training progresses. Parameters receiving large or frequent gradients experience faster learning rate decay. This adaptation is useful for problems with sparse gradients, as infrequent updates receive larger effective step sizes. A drawback is that $G_{t,ii}$ increases monotonically, causing the effective learning rate to eventually become very small, potentially stopping learning prematurely.

Adam

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) combines adaptive learning rates with momentum. It maintains two exponential moving averages (EMAs) for each parameter. The first moment estimate, $m_t$, tracks the mean of the gradients. The second moment estimate, $v_t$, tracks the uncentered variance of the gradients. Given the gradient $g_t = \nabla \ell(w_{t-1})$, these estimates are updated as:

\[\begin{aligned} m_t &= \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) g_t \\ v_t &= \beta_2 v_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) g_t^2 \end{aligned}\]The operations are element-wise, and $\beta_1, \beta_2$ are decay rates (e.g., $0.9$ and $0.999$). Since $m_0=0$ and $v_0=0$, these estimates are biased towards zero in early iterations. For example, if $g_t=g$ is constant, $m_t = (1 - \beta_1^t) g$, showing the estimate is scaled by $(1 - \beta_1^t)$. Adam corrects this initialization bias:

\[\begin{aligned} \hat{m}_t &= \frac{m_t}{1 - \beta_1^t} \\ \hat{v}_t &= \frac{v_t}{1 - \beta_2^t} \end{aligned}\]The bias correction factors approach 1 as $t$ increases. The parameter update uses these corrected estimates:

\[w_t = w_{t-1} - \alpha \frac{\hat{m}_t}{\sqrt{\hat{v}_t} + \epsilon}\]Here, $\alpha$ is the step size (e.g., $0.001$) and $\epsilon$ prevents division by zero (e.g., $10^{-8}$). The term $\alpha / (\sqrt{\hat{v}_t} + \epsilon)$ acts as an adaptive learning rate, decreasing for parameters with large second moment estimates. The term $\hat{m}_t$ incorporates momentum. Adam involves several hyperparameters ($\alpha, \beta_1, \beta_2, \epsilon$) whose tuning can affect performance (Choi et al., 2020). PyTorch defaults are often $\beta_1=0.9, \beta_2=0.999, \epsilon=10^{-8}$.

AdamW

Standard L2 regularization adds $\frac{\lambda}{2}|w|_2^2$ to the loss $L(w)$. The gradient becomes $g_t = \nabla \ell(w_{t-1}) + \lambda w_{t-1}$. In SGD, this is equivalent to weight decay:

\[w_t = (1 - \alpha\lambda)w_{t-1} - \alpha\nabla \ell(w_{t-1})\]Loshchilov and Hutter (2019) noted this equivalence fails for Adam because the regularization term $\lambda w_{t-1}$ within $g_t$ gets adaptively scaled by $1/\sqrt{\hat{v}_t}$, making the effective weight decay dependent on gradient history.

AdamW decouples weight decay from the adaptive update mechanism. The AdamW update first computes the gradient $g_t = \nabla \ell(w_{t-1})$. It updates the moment estimates $m_t$ and $v_t$ using $g_t$, and computes the bias-corrected $\hat{m}_t$ and $\hat{v}_t$ as in Adam. The parameter update then applies weight decay directly to the weights before incorporating the scaled momentum term:

\[w_t = (1 - \alpha\lambda)w_{t-1} - \frac{\alpha}{\sqrt{\hat{v}_t} + \epsilon}\hat{m}_t\]This formulation applies a consistent weight decay factor $\alpha\lambda$ (or sometimes just $\lambda$ in implementations) to all parameters. The authors claim this decoupling improves generalization and makes the optimal weight decay factor less dependent on the learning rate compared to standard Adam with L2 regularization.

Figure Interpretations

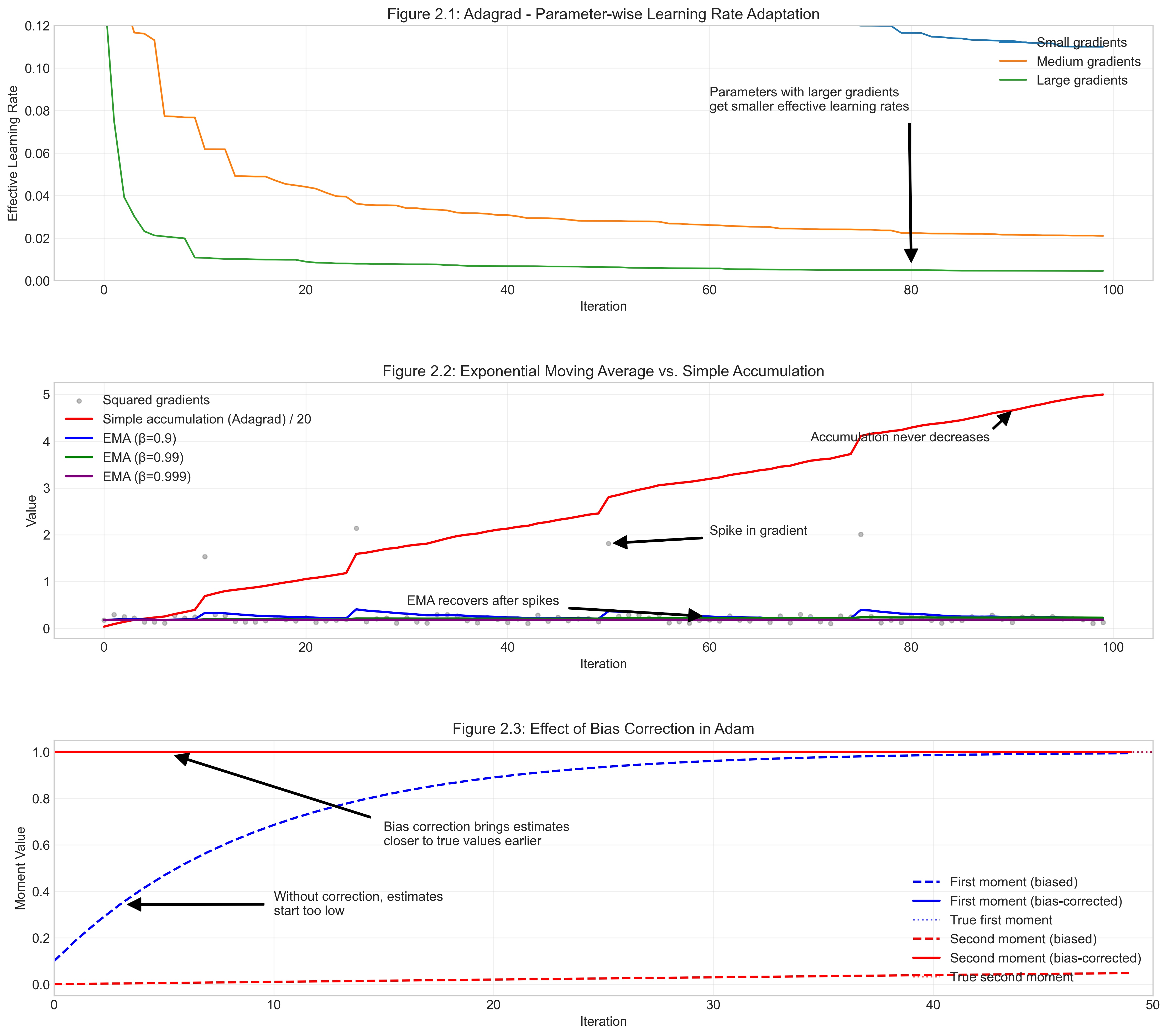

Figure 2.1 shows Adagrad’s effective learning rate $\alpha / \sqrt{G_{t,ii}+\epsilon}$ decreasing over time. The decrease is faster for the parameter with larger historical gradients (green line). This illustrates per-parameter adaptation but also the potential for learning to stall.

Figure 2.2 compares the denominator terms. Adagrad’s sum of squares $G_{t,ii}$ (red line) increases without bound. Adam’s EMA $v_t$ (blue, green, purple lines for different $\beta_2$) stabilizes, forgetting older gradients. This allows Adam to avoid Adagrad’s vanishing learning rates. Higher $\beta_2$ implies more smoothing and slower adaptation to gradient changes.

Figure 2.3 shows the effect of Adam’s bias correction. Uncorrected moments $m_t, v_t$ (dashed lines) start near zero and increase slowly. Bias-corrected moments $\hat{m}_t, \hat{v}_t$ (solid lines) approach their true values faster, enabling more effective updates early in training, especially when $\beta_1, \beta_2$ are close to 1.

Okay, here is a revised “Theoretical Analysis” section incorporating your feedback.

Convergence Analysis

This section presents convergence bounds for Adagrad and Adam, primarily adapted from Défossez et al. (2022). These results provide insights into the algorithms’ behavior, although they may not represent the tightest possible bounds currently known. We use this source because its analysis offers a relatively clear comparison between the methods. Analyzing Adam, in particular, has proven challenging; the proof in the original Adam paper (Kingma & Ba, 2015) was later found incorrect, leading to subsequent work like AMSGrad (Reddi et al., 2019) and refined analyses (Ward et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2019a,b) establishing convergence under specific conditions.

Assumptions

The analysis requires assumptions about the objective function $L(w) = \mathbb{E}_{z \sim \mathcal{D}}[\ell(w, z)]$.

- Lower Bounded: $L(w) \geq L_* $ for some finite $L_* $. This prevents divergence.

- Bounded Gradients ($\ell_\infty$): $||\nabla \ell(w, z)||_\infty \leq R$ for all $w, z$. The coordinate-wise nature of adaptive updates makes the $\ell_\infty$ norm (maximum absolute coordinate value) a useful bound for analysis.

- Smoothness ($L$-smooth): $||\nabla L(w) - \nabla L(w’)||_2 \leq L||w - w’||_2$. The gradient of the objective $L$ does not change arbitrarily quickly.

Convergence Measure

For potentially non-convex objectives, the goal is often to find stationary points where $\nabla L(w) \approx 0$. Convergence is measured by bounding the expected squared norm of the gradient, $\mathbb{E}[||\nabla L(w)||^2]$. Because iterates $w_t$ are random due to stochastic sampling, bounds are typically derived for $\mathbb{E}[||\nabla L(w_{\tau_N})||^2]$, where $\tau_N$ is a randomly selected index from ${0, …, N-1}$. The sampling distribution for $\tau_N$ might be uniform or weighted depending on the algorithm and analysis (e.g., weighting recent iterates less for Adam with momentum).

The resulting bounds often take the form:

\[\mathbb{E}[\|\nabla L(w_{\tau_N})\|^2] \leq \text{Term}_1(\text{Initial Error}) + \text{Term}_2(\text{Noise})\]This structure mirrors the error decomposition seen in SGD analysis (Lectures 6/7), where $\text{Term}_1$ depends on the initial suboptimality $L(w_0) - L_* $ and decreases with iterations $N$, while $\text{Term}_2$ reflects the impact of stochastic gradient noise.

Adagrad Result

For Adagrad with constant step size $\alpha$, Défossez et al. (2022) show (using uniform sampling for $\tau_N$):

\[\mathbb{E}[\|\nabla L(w_{\tau_N})\|^2] \leq \frac{2R(L(w_0) - L_*)}{\alpha\sqrt{N}} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}\left(4dR^2 + \alpha dRL\right)\ln\left(1 + \frac{NR^2}{\epsilon}\right)\]The bound converges at a rate of $O(d \ln(N) / \sqrt{N})$. The initialization term decays as $O(1/\sqrt{N})$. The noise term includes the dimension $d$. This dimension dependence appears worse than typical SGD bounds, which depend on gradient variance

\[\sigma^2 = \mathbb{E}[\|\nabla \ell(w, z) - \nabla L(w)\|_2^2].\]However, if gradient components are roughly independent and bounded by $R$, the variance scales like $||g||_2^2 \leq d R^2$ (e.g., if the noise in the gradient is like a Gaussian random variable). In such cases, the $d$ dependence in Adagrad’s bound is comparable to the dependence on variance in SGD bounds. If gradients are sparse (many components near zero), then $||g||_2^2$ could be much smaller than $dR^2$, potentially making Adagrad’s bound looser than SGD’s. Adagrad converges with constant $\alpha$ because the adaptive scaling $1/\sqrt{G_{t,ii}}$ provides implicit dampening.

Adam Result

The analysis of Adam in Défossez et al. (2022) uses a slightly modified step size $\alpha_t = \alpha(1-\beta_1) \sqrt{(1-\beta_2^t)/(1-\beta_2)}$, removing the first moment bias correction for analytical simplicity. For this variant with no momentum ($\beta_1 = 0$) and uniform sampling for $\tau_N$:

\[\mathbb{E}[\|\nabla L(w_{\tau_N})\|^2] \leq \frac{2R(L(w_0) - L_*)}{\alpha N} + E \cdot \left(\frac{1}{N}\ln\left(1 + \frac{R^2}{(1-\beta_2)\epsilon}\right) - \ln(\beta_2)\right)\]where $E = \frac{4dR^2}{\sqrt{1-\beta_2}} + \frac{\alpha dRL}{1-\beta_2}$. The initialization term decays faster than Adagrad’s, at $O(1/N)$. However, the noise term contains a constant component $-E \ln(\beta_2)$ which does not decay with $N$. This creates a “noise floor,” meaning Adam with fixed hyperparameters does not converge to a stationary point according to this bound.

Défossez et al. summarize the relationship:

Adam and Adagrad are twins. Our analysis highlights an important fact: Adam is to Adagrad like constant step size SGD is to decaying step size SGD. While Adagrad is asymptotically optimal, it also leads to a slower decrease of the term proportional to $L(w_0) - L^*$, as $1/\sqrt{N}$ instead of $1/N$ for Adam. During the initial phase of training, it is likely that this term dominates the loss, which could explain the popularity of Adam for training deep neural networks rather than Adagrad. With its default parameters, Adam will not converge. It is however possible to choose $\beta_2$ and $\alpha$ to achieve an asymptotic convergence rate of $O(d\ln(N)/\sqrt{N})$…

Specifically, scheduling $\alpha \propto 1/\sqrt{N}$ and $\beta_2 = 1 - 1/N$ recovers the $O(d\ln(N)/\sqrt{N})$ rate, matching Adagrad.

Impact of Momentum

Introducing momentum ($\beta_1 > 0$) worsens the theoretical bounds presented by Défossez et al. The bound takes a similar form but involves constants that increase with $\beta_1$, roughly scaling with factors like $(1-\beta_1)^{-1}$, and uses a reduced effective iteration count $\tilde{N} < N$. While this $O((1-\beta_1)^{-1})$ dependence is better than prior analyses, it still implies $\beta_1 = 0$ gives the best worst-case guarantee.

This creates a gap between theory and practice, as momentum is widely used and empirically beneficial with Adam. Current convergence bounds do not seem to fully capture momentum’s advantages. Recent work analyzing Adam variants reinforces this gap; for example, Guo et al. (2023) state about their bounds:

“No better result with momentum… the tightest bound is achieved when $\beta_1 = 0$… This contradicts with the common wisdom that momentum helps to accelerate… we view this as a limitation of our work and defer proving the benefit of momentum in Adam as a future work.”

Thus, while momentum empirically helps Adam navigate complex loss landscapes, existing worst-case analyses suggest it hinders convergence rate guarantees.

Practical Implementation

PyTorch Implementation

Let’s see how to implement the optimization algorithms we’ve discussed using PyTorch. PyTorch provides built-in implementations of these optimizers in its torch.optim module, but understanding their manual implementation helps clarify the underlying mechanisms.

We’ll start with a minimal implementation of Adagrad. The core logic involves accumulating squared gradients and using them to scale the learning rates:

def adagrad_update(params, grads, state, lr=0.01, eps=1e-8):

"""

Basic Adagrad implementation

Args:

params: List of parameters

grads: List of gradients

state: List of accumulators for squared gradients

lr: Learning rate

eps: Small constant for numerical stability

"""

for i, (param, grad) in enumerate(zip(params, grads)):

# Initialize accumulator if needed

if len(state) <= i:

state.append(torch.zeros_like(param))

# Accumulate squared gradients

state[i].add_(grad * grad)

# Compute update

std = torch.sqrt(state[i] + eps)

param.addcdiv_(grad, std, value=-lr)

return params, state

This implementation follows the Adagrad update rule we defined earlier. For each parameter, we maintain a corresponding state vector that accumulates the squared gradients. We then compute the square root of this accumulation, add a small epsilon for numerical stability, and use this to scale the gradient before applying the update.

Next, let’s implement Adam, which adds momentum and bias correction:

def adam_update(params, grads, m_state, v_state, lr=0.001,

beta1=0.9, beta2=0.999, eps=1e-8, t=1):

"""

Basic Adam implementation

Args:

params: List of parameters

grads: List of gradients

m_state: List of first moment estimators

v_state: List of second moment estimators

lr: Learning rate

beta1: Exponential decay rate for first moment

beta2: Exponential decay rate for second moment

eps: Small constant for numerical stability

t: Current iteration number (starting from 1)

"""

# Compute bias correction terms

bias_correction1 = 1 - beta1**t

bias_correction2 = 1 - beta2**t

for i, (param, grad) in enumerate(zip(params, grads)):

# Initialize moment estimates if needed

if len(m_state) <= i:

m_state.append(torch.zeros_like(param))

v_state.append(torch.zeros_like(param))

# Update biased first moment estimate

m_state[i].mul_(beta1).add_(grad, alpha=1-beta1)

# Update biased second moment estimate

v_state[i].mul_(beta2).add_(grad * grad, alpha=1-beta2)

# Correct bias in first moment estimate

m_hat = m_state[i] / bias_correction1

# Correct bias in second moment estimate

v_hat = v_state[i] / bias_correction2

# Update parameters

param.addcdiv_(m_hat, torch.sqrt(v_hat) + eps, value=-lr)

return params, m_state, v_state

This implementation captures the key elements of Adam: maintaining exponentially moving averages of gradients and squared gradients, applying bias correction, and using these estimates to adapt the learning rate for each parameter.

For AdamW, we modify the Adam implementation to decouple weight decay from the adaptive update:

def adamw_update(params, grads, m_state, v_state, lr=0.001,

beta1=0.9, beta2=0.999, eps=1e-8, weight_decay=0.01, t=1):

"""

Basic AdamW implementation

Args:

params: List of parameters

grads: List of gradients

m_state: List of first moment estimators

v_state: List of second moment estimators

lr: Learning rate

beta1: Exponential decay rate for first moment

beta2: Exponential decay rate for second moment

eps: Small constant for numerical stability

weight_decay: Weight decay coefficient

t: Current iteration number (starting from 1)

"""

# Compute bias correction terms

bias_correction1 = 1 - beta1**t

bias_correction2 = 1 - beta2**t

for i, (param, grad) in enumerate(zip(params, grads)):

# Initialize moment estimates if needed

if len(m_state) <= i:

m_state.append(torch.zeros_like(param))

v_state.append(torch.zeros_like(param))

# Apply weight decay (decoupled from adaptive updates)

param.mul_(1 - lr * weight_decay)

# Update biased first moment estimate

m_state[i].mul_(beta1).add_(grad, alpha=1-beta1)

# Update biased second moment estimate

v_state[i].mul_(beta2).add_(grad * grad, alpha=1-beta2)

# Correct bias in first moment estimate

m_hat = m_state[i] / bias_correction1

# Correct bias in second moment estimate

v_hat = v_state[i] / bias_correction2

# Update parameters

param.addcdiv_(m_hat, torch.sqrt(v_hat) + eps, value=-lr)

return params, m_state, v_state

The key difference in AdamW is the addition of the direct weight decay step, which multiplies each parameter by (1 - lr * weight_decay) before the adaptive update. This decouples the regularization effect from the adaptive learning rates.

In practice, we typically don’t implement these optimizers manually but use PyTorch’s built-in implementations. Here’s how to use them:

import torch

import torch.optim as optim

# Define a model

model = torch.nn.Linear(10, 1)

# Create optimizers

adagrad_opt = optim.Adagrad(model.parameters(), lr=0.01)

adam_opt = optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=0.001, betas=(0.9, 0.999), eps=1e-8)

adamw_opt = optim.AdamW(model.parameters(), lr=0.001, betas=(0.9, 0.999),

eps=1e-8, weight_decay=0.01)

# Training loop

for X, y in dataloader:

# Zero gradients

adam_opt.zero_grad()

# Forward pass and compute loss

output = model(X)

loss = criterion(output, y)

# Backward pass

loss.backward()

# Update parameters

adam_opt.step()

PyTorch’s implementations include additional features like parameter groups (allowing different hyperparameters for different layers) and various optimizations for efficiency. The implementations match the mathematical formulations we’ve discussed, with minor variations to handle edge cases and improve numerical stability.

Example Experiment

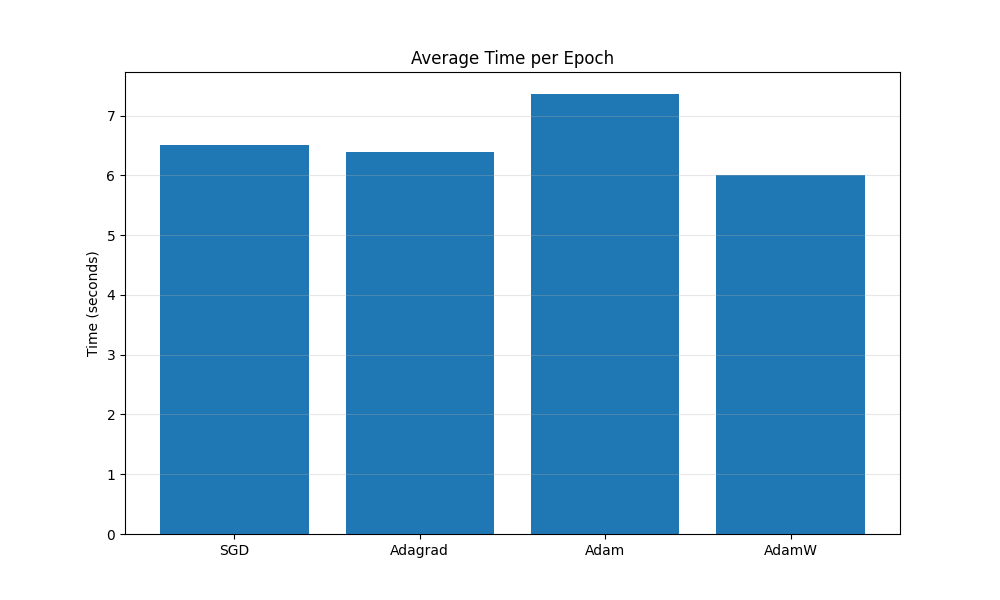

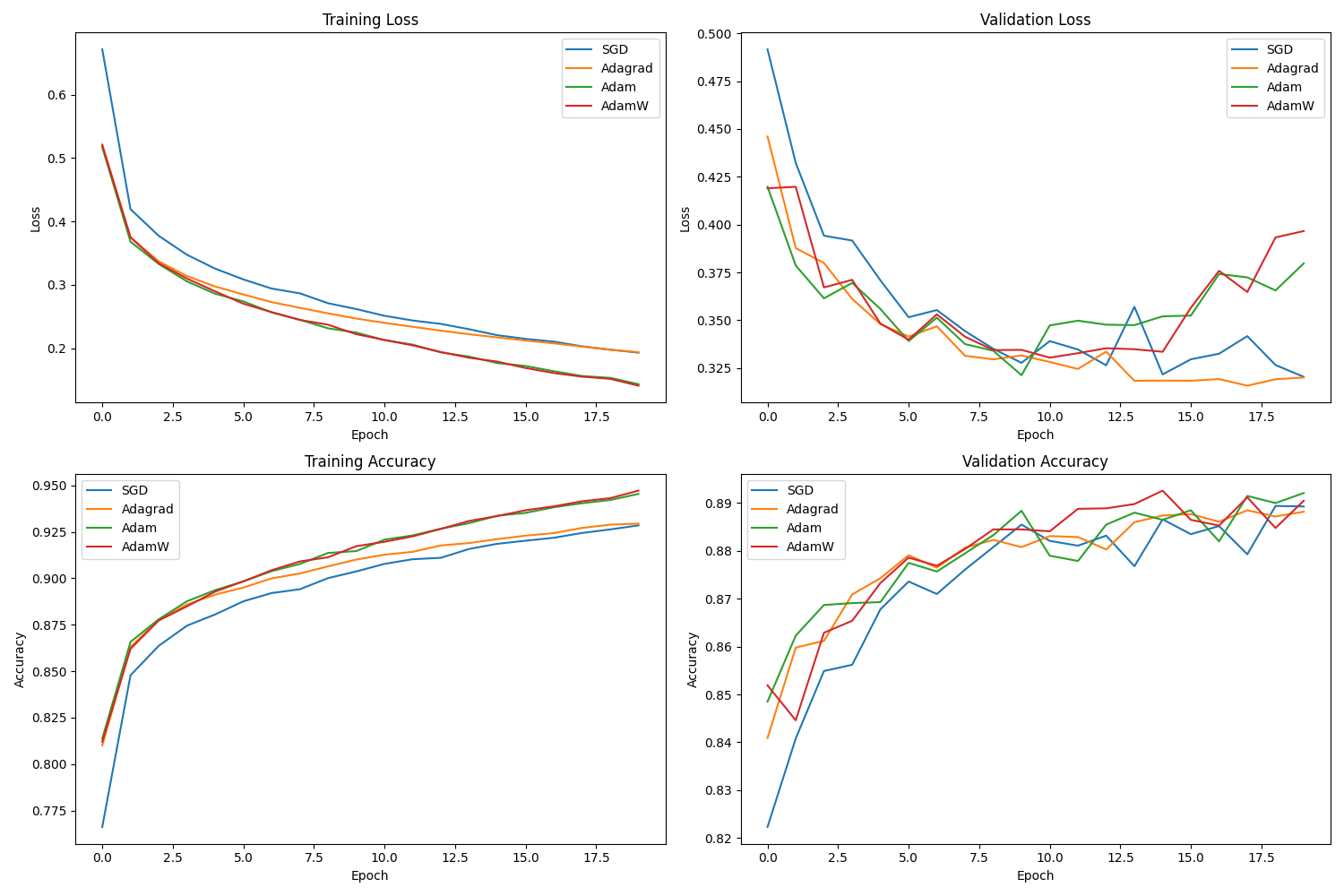

The provided code compares SGD (with momentum=0.9, wd=1e-4), Adagrad, Adam, and AdamW (wd=1e-4) on Fashion MNIST classification using a simple feedforward network. It trains each optimizer for 20 epochs using specified learning rates (SGD/Adagrad: 0.01, Adam/AdamW: 0.001) and plots training/validation loss and accuracy, along with average time per epoch. The full script and interactive notebook are available via the colab.

The timing plot shows comparable time per epoch for all methods in this specific setup. The performance plots indicate that for this model, dataset, and hyperparameter choice, the adaptive methods achieved lower loss and higher accuracy more quickly than SGD initially. Final performance appears similar among the adaptive methods. Adam and AdamW tracks are very close.

Empirical optimizer comparisons are sensitive. Performance depends strongly on the model architecture, dataset characteristics, and especially hyperparameter tuning (learning rate, $\beta$ values, weight decay). Results from one experiment do not guarantee general performance differences. Robust benchmarking requires testing across multiple tasks and extensive hyperparameter optimization (e.g., Algoperf benchmark, Choi et al., 2020).

References

[1] Duchi, J., Hazan, E., & Singer, Y. (2011). Adaptive subgradient methods for online learning and stochastic optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12(Jul), 2121-2159. Link

[2] Tieleman, T., & Hinton, G. (2012). Lecture 6.5—RMSProp: Divide the gradient by a running average of its recent magnitude. COURSERA: Neural Networks for Machine Learning. Link

[3] Kingma, D. P., & Ba, J. (2015). Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). Link

[4] Loshchilov, I., & Hutter, F. (2019). Decoupled weight decay regularization. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). Link

[5] Défossez, A., Bottou, L., Bach, F., & Usunier, N. (2022). A simple convergence proof of Adam and Adagrad. Transactions on Machine Learning Research (TMLR). Link

[6] Zhang, G., Li, L., Nado, Z., Martens, J., Sachdeva, S., Dahl, G., Shallue, C., & McAllester, D. (2019). Which algorithmic choices matter at which batch sizes? Insights from a noisy quadratic model. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). Link

[7] Choi, D., Shallue, C. J., Nado, Z., Lee, J., Maddison, C. J., & Dahl, G. E. (2020). On empirical comparisons of optimizers for deep learning. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). Link